Edita Morris

– a short biography by Christopher Toll

Edita Morris – before her marriage Edith Toll – was born in Örebro, Sweden, on 5 March 1902. She was the youngest of four daughters of the agronomist Reinhold Toll and his first wife Alma Prom-Möller and grew up in the country in South Sweden at her grandmother’s farm and in Stockholm, where she was educated by a divorced strong-willed mother, and at a good girls’ school. The family was noble and poor, a combination that entailed great efforts and privations in secret, in order to enable the girls to take the place in the society of Stockholm in the twenties to which their name and education entitled them. Already Edith’s teacher in Swedish encouraged her to write, and a tragic accident that killed one of her sisters might have stirred her wish to express her feelings. But writing gave no income. So Edith got work at the Army Council as a secretary and became engaged to a young lieutenant of a noble family.

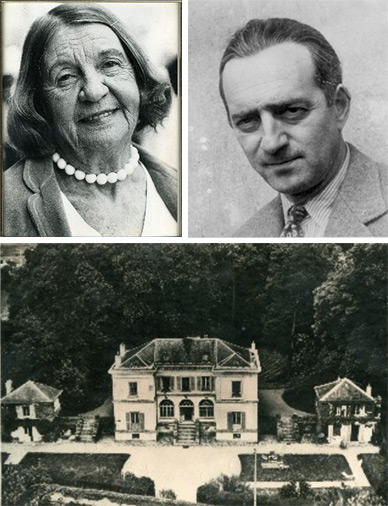

But destiny intervened in the person of young Ira Morris, son of a similarly named American millionaire and envoy to Stockholm. He took her away, in 1925, from the fiancé, the Army Council and Stockholm to Nesles, a château in France which his father gave to the couple. Himself a writer, Ira Morris got her to realize her dream of writing, and under her new name Edita Morris she published a number of short stories in American literary magazines. Ira Morris was opposed to his rich and ostentatious parents and got Edita interested in political and social questions which inspired her to many books.

The best known is The Flowers of Hiroshima about the victims of the atomic bomb whom she met when she visited Hiroshima in 1955. This book, which won the Albert Schweitzer Prize in 1961, has been turned into an opera, Hollywood bought the film rights (but the film was never produced), and it was translated into so many languages (39?) that she used to say that only Dr. Spock had surpassed her in this respect. She wrote in English but her books have been translated into her Swedish mother tongue and into many other languages. Among them are The Solo Dancer, about the son of an Indonesian rice peasant, A Happy Day, Love to Vietnam, How are you, I hope well about a black maid in Jamaica and her white mistress, and Kill the beggars! about poverty in South America. She also wrote two autobiographical works, The Strait Jacket and The Seventy Years’ War. Her best novel was Life, wonderful life!, a revised edition of the first part of My darling from the lions (six reprints in the USA and seven foreign editions). The novel is built upon her recollections of the happy country life at the farm of her grandmother. ”It is fresh as mountain air”, one critic said, ”and youth sings through it.” It was, however, in the short story that her mastership reached its peak and caused critics to compare her to Katherine Mansfield. Her first book was a collection of short stories entitled Birth of an old lady and other stories, other collections were Three who loved, Dear me and other tales from my native Sweden. Some of her stories have been staged. She kept writing until her death and was inspired by many new subjects, such as Linnaeus, the Polar explorer Eduard Toll who disappeared in the ice in 1902, the Vikings: she wanted to turn everything into a story.

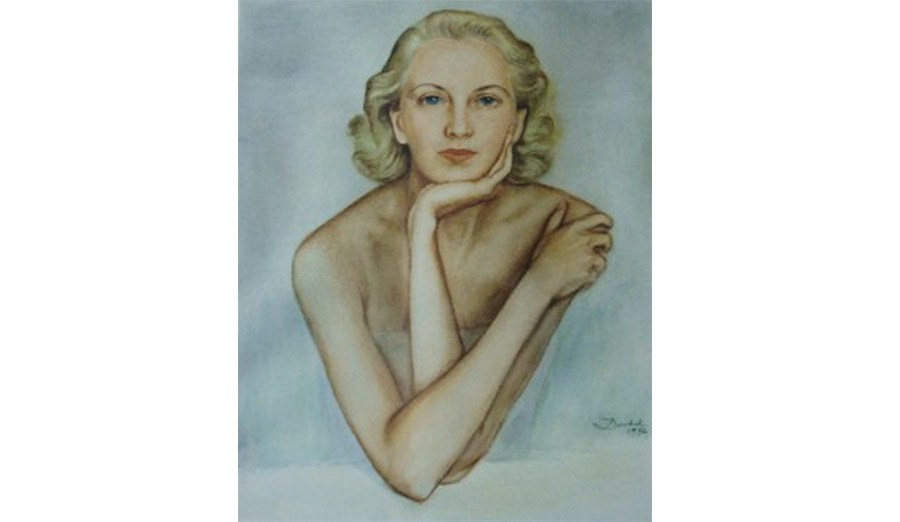

Her own life was perhaps her best story, about the poor Swedish girl who became a famous writer in English and a well known figure in the world of literature and art. Through her friendship with the Swedish painter Nils Dardel, who made some beautiful portraits of her, she got to know, among others, Georges Braque and through this acquaintance it happened that she spent her last years in a flat opposite Braque’s house in the street in Paris which now bears his name.

But most thrilling were the contrasts in her life and personality: between the poverty and the nobility in her youth, between the wealth and the socialism in her married life, between a gradually older and more conservative well-born lady, a woman of the world, equally at home in New York, Mexico City, Paris, London, Athens and Stockholm, with a faithful driver and a perfect cook, disapproving of the long hair, slovenly dress and bad manners of the younger generation – and a writer who in several of her books campaigned against poverty, starvation and oppression and for peace and disarmament, and in that capacity spent time in the company of long-haired and leftist youths in jeans and was invited to visit Socialist countries such as the Soviet Union and Communist China.

She died in Paris on 14 March 1988 – both her husband Ira Morris and their son Ivan Morris, a distinguished professor of Japanese at Columbia University and a well-known translator of Japanese literature, had died before her. They all three of them lie buried in the park of their beloved Nesles in Brie. Edita Morris left her property to the Edita and Ira Morris Hiroshima Foundation for Peace and Culture. Except for a half-sister in London, now also dead, she had no closer relatives than her Toll family in Sweden.

There is a new book about Edita Morris by Monica Braw comming up. Read more about it at: monicabraw.se

Top: Edita Morris and Ira Morris

Below: Nesles-la-Gilberde, Seine-et Marne, France. Home of Edita and

Ira Morris